Ruling Class Solidarity: Conflict & Growth at SFMOMA Reexamined

How museum collector-trustees recapture charitable donations.

One day in 1999, Charles Schwab and Donald Fisher walked into a very exclusive pawnshop. The San Francisco businessmen, respectively banking and retail magnates, were in the vault of Fukuoka City Bank in Japan, browsing the collateral—blue-chip art used to secure defaulted loans—in part for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. To decide who would buy what, Schwab and Fisher allocated numbers to works by famed modernists Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein, Alexander Calder and Andy Warhol, and drew from a hat12. SFMOMA announced ten works acquired for $60 million3. The bank boasted of some $17 million in profits4.

Underlying this scene was the construction of artwork as an asset class. Borrowers used art to secure loans, siphoning from the objects what they would call liquidity, say, capital to diversify an investment portfolio or pursue near-term speculation. By accepting the art as collateral, the bank conferred upon the canvasses and sculptures a status akin to real-estate or other securities. The borrowers’ default, followed by a market upswing, then set the stage for a profitable flip. And the wealthy collector-trustees of a growing museum vindicated the bank’s wager. Fisher considered this convergence of collecting and investing a guiding light for his own art-buying.

“Well, I look at it as an investment, not because I sell it,” Fisher told a UC Berkeley interviewer in 2007, two years before his death, when the Gap cofounder was deciding the fate of his and his wife Doris Fisher’s modern art collection, worth an estimated $1 billion5. “But there’s a psychic enjoyment knowing you did something right and it’s worth more than what you paid for it.”

The Financialization of Art

Art has uses other than collateralizing bank loans. It can be acquired by limited partnerships on behalf of institutional investors such as pension funds; a public employee’s retirement might indirectly hinge on an auction at Christie’s. It can be loaned by those same limited-partnerships for exhibition, viewers unaware. It can do a lot for tax avoidance, not only through outright donation. It can be bought and sold within a trust from which the owner derives an income, untrimmed by capital gains taxes. It can be exhibited in Oregon in order to avoid a use tax. It can be guaranteed a certain auction price by investors who earn a fee if it fetches more than that price. It can be donated to a charitable entity without ever leaving the collector’s home.

Financialization refers to the stage of capitalism since the 1980s in which profit-making from existing assets outpaces other sectors of the economy. Economists tend to measure it by financial services generating a runaway share of national income. It is the coup of the neoliberal ideology that defines freedom in terms of market transactions, enshrining financial actors and motives in political rule. Most of us experience it directly in the form of debt, or as a hedge-fund landlord. It’s why manufacturers are now lenders as well; it enables capitalists to extract money from workers in ways other than selling them particular products. In the arts, as the earlier examples show, it looks like the financial instruments familiar from private equity and publicly-traded securities adapting to ingest artworks and hoard their profit yield.

William Friedkin’s movie To Live and Die in LA, released in 1985, as modern art’s association with an ascendant economic elite cemented in popular culture, highlights the irrelevance of individual artists under financialization—a system designed to proceed without them. We first encounter Rick Masters, the artist-forger antagonist played by Willem Dafoe, burning one of his own canvases. In his next appearance, Masters applies his skills to counterfeit currency, in a striking moment revealing the bills’ positive image on a metal sheet with only his breath. Masters, however, collects none of the fictitious capital he summons into generative circulation. Absent in montages of cash changing hands around Los Angeles is the artist-forger himself.

Since the 2008 recession, profit-making from art as an asset class has only continued to consolidate within a remote strata of the ultra-wealthy. Global art sales have grown 5 percent, reaching $64.1 billion in 20196. Art investment funds reached $2.1 billion assets under management in 2012, and the balance of art-secured loans reached some $17-$20 billion in 20177. As finance professionals transform art into an alternative asset class, their expertise supplants the humanities-related knowledge conventionally considered paramount in the field. Most banks and wealth managers catering to ultra-high networth individuals (UHNWIs, in industry parlance) offer “art advisory services,” probably including connections to the nearest freeport8.

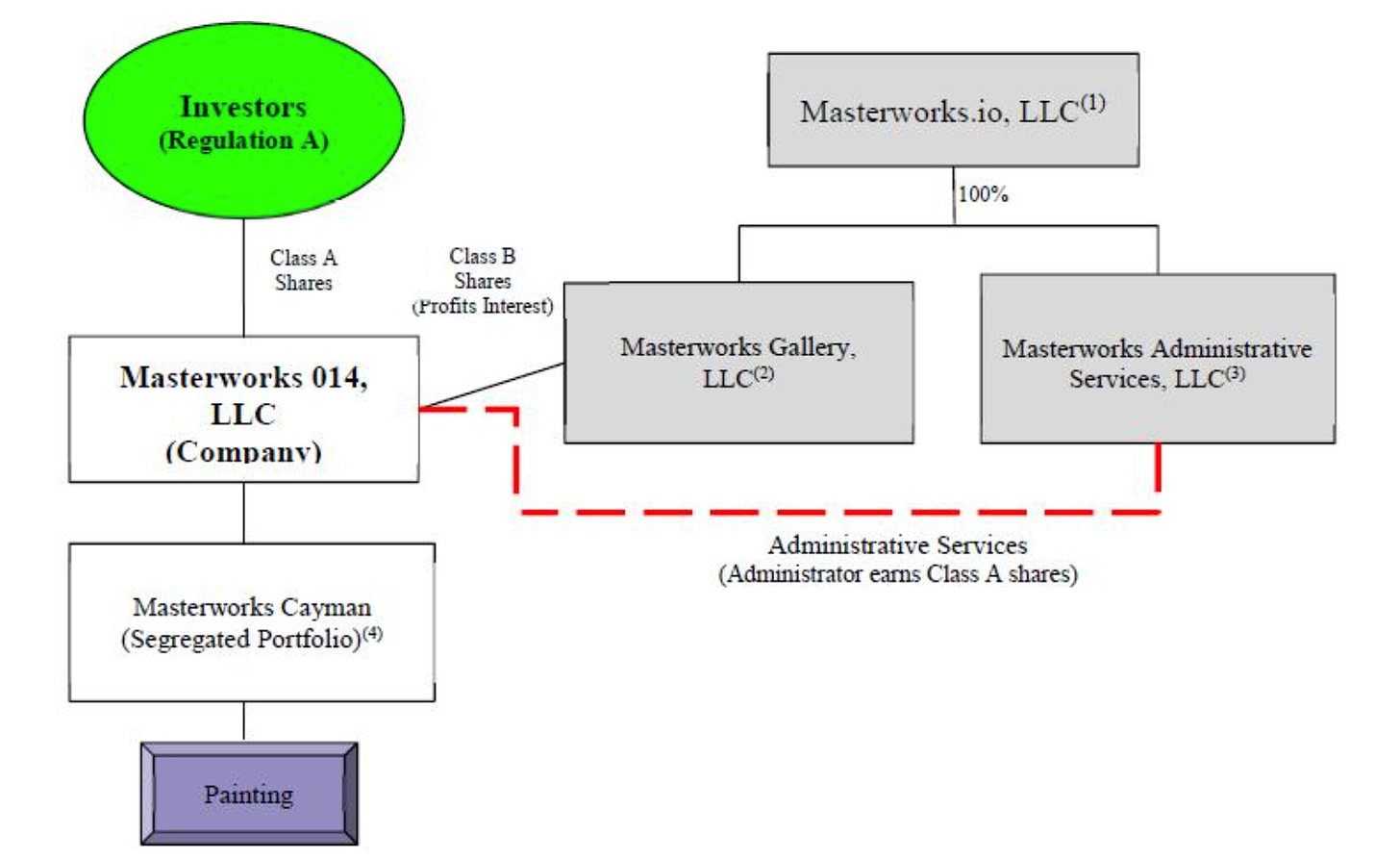

Museums help out. Institutions are openly selling valuable works in order to raise funds, officials say, for diversifying permanent collections—an attempt to ennoble as progressive their close ties to art market speculators9. Business publications endorse the idea of museum art investment collections, whereby institutions set-aside works to trade for profit. In 2020, the Association of American Museum Directors reversed its position against selling art from collections10. This is the trend obscured in the popular debate about museums’ stewardship responsibilities. Art investment funds provide stealth examples. In 2020, the limited liability company Masterworks 014 formed to facilitate investment in abstract painter Joan Mitchell’s 1962 canvas Rhubarb11. The document soliciting $5 million from investors cites Mitchell’s upcoming SFMOMA and Baltimore Museum of Art retrospective among the factors likely to deliver returns. Will Rhubarb appear in the exhibition itself?

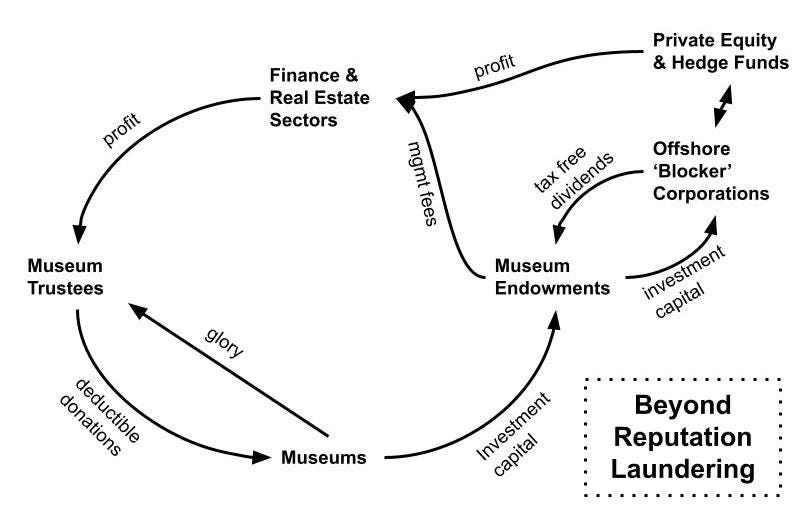

Diminished government support for museums has increased their dependence on UHNWI collector-trustees and the financial services underlying these patrons’ capital accumulation. In 2014, 4 percent of arts funding came from public sources. Earned-income (admissions, totes, etc.) and indirect public support in the form of tax breaks have almost fully supplanted public support, shifting institutional priorities at the highest levels12. The post-millennial building boom, for example, occurred while museum attendance declined, instead reflecting efforts to court donors13. Collector-trustees are positioned to dictate self-serving terms for loaning or donating art and, in a turn I’ll describe at SFMOMA, steer endowment investments towards private equity and hedge funds, instrumentalizing museums in our finance-led economic growth regime.

Collector-trustees are consolidating power at major museums as artists, activists and scholars works to show these institutions’ role in reproducing whiteness as hegemonic. No longer does a nonprofit status alone convey virtue. Without this shroud, charities are more clearly seen as sites of social conflict perpetuating inequality. Meager wages and precarious employment terms are driving union campaigns. Activists are scrutinizing trustee wealth. Yet museums do not only burnish the reputations of the ultra-wealthy, as activists lately tend to stress, or passively reflect broader economic trends. Not least as sources of investment capital and fees for the financial sector, they actively sharpen inequality. They’ve become vehicles for the ultra-wealthy to advance their ruling-class interests, diverting the benefits of charitable-giving to themselves and the managers of their vast fortunes.

Racialized Class Conflict

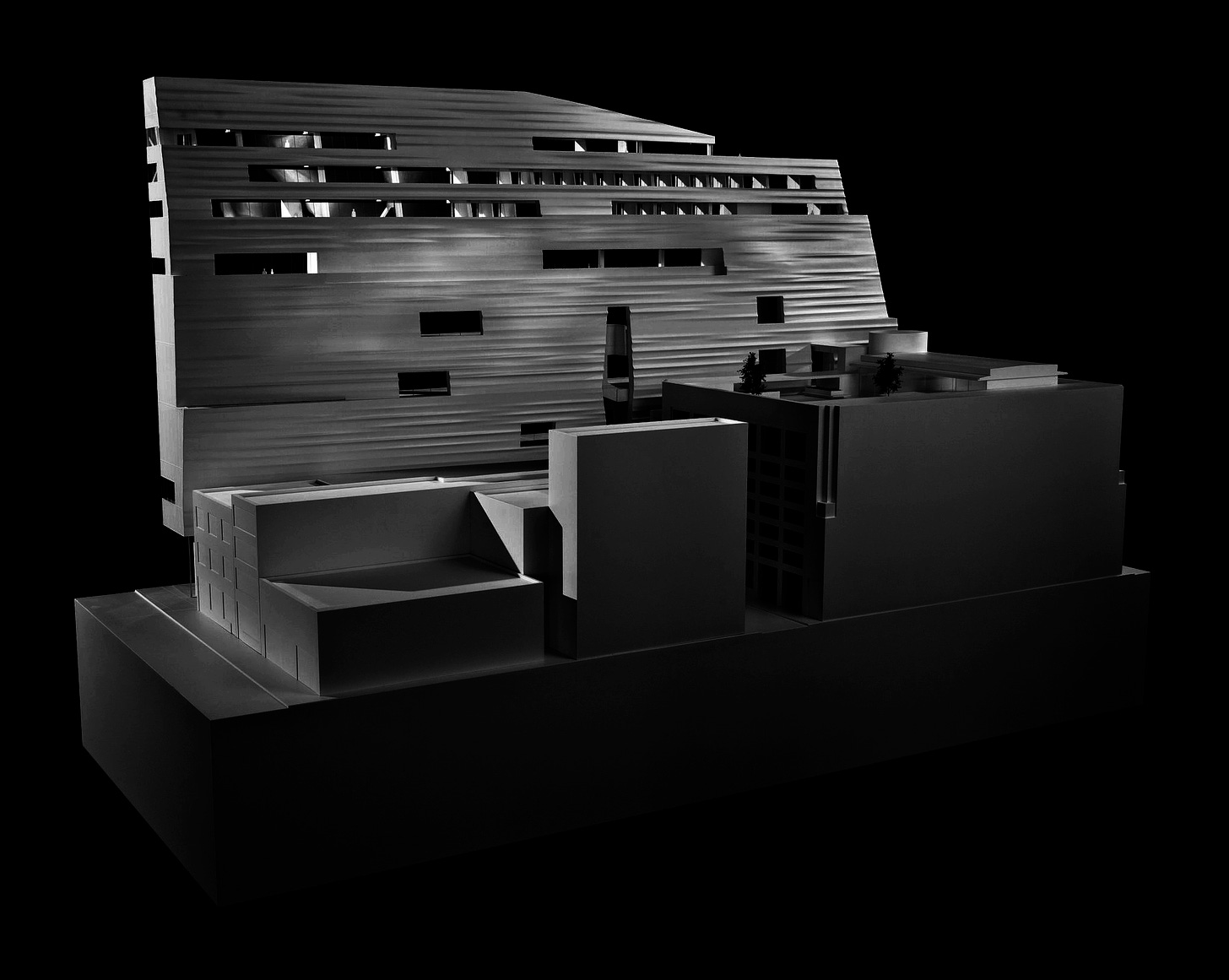

This is the context in which to examine SFMOMA’s growth since Fisher and Schwab walked into the Fukuoka City Bank. The museum reopened in 2016 after a $305 million Snøhetta expansion more than doubled its exhibition space and operating budget. Some 60 percent of gallery space, however, was reserved for predominantly works loaned from the Fisher Collection—a century-long deal enshrining the Gap founder’s heavily male, German and New York-centric view of post-war art across three floors; no more than 25 percent of works on view, Fisher stipulated, may come from another source14. Fisher seemed aware of SFMOMA as a fitting vehicle for his white-canonical collection when, in 2007, he contrasted the museum with “special single-interest groups” behind institutions such as the Museum of the African Diaspora.

The Fisher loan restrictions drew strong criticism, mostly along the lines of diminished curatorial autonomy. The inequality produced by the racialized class conflict embedded in this institutional growth attracted less attention. Between 2004 and 2018, the hourly wage for frontline workers, the most racially diverse segment of museum staff, grew at half the rate of the city’s minimum wage. In 2016, when San Francisco’s minimum wage reached $13/hour, SFMOMA coat-checkers started at $13.72/hour. In this same period, SFMOMA’s board awarded director Neal Benezra and senior curator Gary Garrels more than $1.3 million in interest-free home loans—necessary perks, Garrels has argued in his own defense, considering the exorbitant San Francisco housing market15. Yet museum officials refused to consider local cost-of-living to determine raises for 245 union-represented employees during 2018 contract negotiations16.

In 2020, the chasm between the museum’s leadership—collector-trustees and their hand-picked executives—and most of its workforce became even more apparent. While the museum was closed due to the pandemic, layoffs and furloughs affected hundreds of workers. The censorship of a Black former employee also spurred two activist groups, No Neutral Alliance and xSFM0MA, to attack the institution’s racial and economic stratification, demanding greater representation and other changes to collections and governance. The pressure ultimately ousted five high-level officials, including Garrels and communications chief Ann von Germeten, who previously worked for Schwab’s bank. Echoing campaigns against museum trustees in New York, xSFM0MA, in particular, eyed the donor walls like monuments to topple.

The museum faced two primary crises in 2020, one of revenue shortfalls and another of political pressure around institutional racism. It responded with a two-pronged management strategy of brutal layoffs and corporate diversity planning, with the latter effectively diverting attention from the former in a prevalent, pernicious form of managerial misdirection. And many current workers believe the layoffs were partly pre-planned cuts implemented under cover of the pandemic. I will come back to the activism around SFMOMA this past year. But first I want to describe some of the little-mentioned, trustee-led financial maneuvers underlying the institution’s uneven growth: Fractional giving, which anticipated the Fisher deal; and the endowment’s post-recession endowment investments, including in the Cayman Islands.

Donation Meets Speculation

The Fukuoka acquisition was one part of SFMOMA’s efforts in the late-1990s to acquire a collection worthy of its new, Mario Botta-designed edifice in the gentrifying South of Market neighborhood. A major part of this same campaign was courting fractional donations of artwork.

The practice allowed collectors to contribute a percentage of their interest in a work to the museum. If the museum received, say, a 10 percent stake, it had the right to exhibit the work 10 percent of the year. But the museum wasn’t obligated to exercise the right, granting donors the tax deduction for work that mostly hung in their homes. The museum, in other words, offered its nonprofit status to enable speculation: Donors could take advantage of the work’s appreciation in value by receiving larger deductions on subsequent fractions. And even the news of a museum acquiring a stake in an artwork enhances the artwork’s value. A donor could even spread the fractional gifts of one work over time sufficient to deduct its full value—or more17.

This was a key pitch to prospective SFMOMA donors. Richard Greene, a tax attorney and longtime trustee, solicited fractional gifts of particular artworks at the behest of Jack Lane, the museum’s director until 199718. “Many of the people were interested in the income tax deduction. It was an extra bonus for them,” Greene said. “What they were all interested in was the ability to continue to display the piece in their homes.” To the museum, a fractional gift represented a tacit if not explicit promise that the collector would over time donate their full interest. Benezra, who started as director in 2002, also stressed the tax advantages: “It was wonderful! … They could receive benefit out of appreciation with their subsequent fractional gifts.” By the mid-2000s, SFMOMA led the nation in the acquisition of fractional gifts, receiving more than 800 stakes19.

Fisher, who looked at art as an investment, not because he sold it, was among the SFMOMA collector-trustees to make fractional gifts. According to Greene, Fisher even explored donating his entire collection as a fractional gift to SFMOMA, intending to gain the benefits while retaining possession. But there was a problem. Chuck Grassley, the Republican senator from Iowa, took a somewhat politically incongruous position against the loophole, calling fractional gifts insufficiently charitable. Fisher hired a lobbyist to attempt to stop Grassley’s legislation effectively ending fractional giving, and Greene personally spoke with senate staff. Benezra, along with Museum of Modern Art director Glenn Lowry, defended the practice in the press.

Grassley’s legislation, embedded in a pension reform bill, passed in 2006. Benezra and other fractional-giving defenders insisted the practice was not abused; it allowed museums to remove works from the prohibitively expensive art market. Abuse, though, was a red herring. The practice isn’t a bulwark against the art market. It integrates speculation and accessions. The effect of the legislation shows as much. The bill didn’t outlaw fractional-giving, it only removed certain incentives: No longer could a donor take a larger deduction from subsequent gifts. So donors could no longer use the museum to benefit from appreciation in value. And in the year after the legislation, according to Benezra, gifts to SFMOMA declined by some 80 percent.

With the defense of fractional giving, Fisher instrumentalized the museum and its philanthropic cachet to pursue a broader political agenda. The Fisher Family, with an estimated family fortune of $8.9 billion, are among the largest political donors in California and the top charter-school supporters in the nation. Litigation revealed the Fishers to be second-largest contributors to Americans for Job Security, a dark money group that deployed massive sums against a California millionaire tax to raise money for public education in 2012, outpaced only by Charles Schwab20. As conservatives, the Fishers and Schwab are not outliers on the SFMOMA board. In the 2016 election, 10 trustees together spent $4.6 million supporting Republican candidates21.

In 2007, after Grassley’s intervention, Fisher then sought approval to build a private museum for his collection in the Presidio of San Francisco, a historic military fort turned tony recreation area. This increasingly-popular model (locally, see Andrew Pilara’s Pier 24), which has also attracted congressional scrutiny, enables founders to deduct the full market value of their art, as well as cash and stocks they donate. Even if the museum is effectively inaccessible to the public, the costs of insuring, conserving and warehousing a collection are tax-free. Preservationists, however, scuttled Fisher’s construction plans for the Presidio. In 2009, shortly before his death, Fisher instead struck the agreement that would bring the Fisher Collection to SFMOMA.

Details of the loan agreement, closely guarded by museum officials, emerged piecemeal in the media, showing elements of fractional giving and private museums alike. The partnership is technically with the Fisher Art Foundation, which lists $1 billion in assets on its most recent tax return, helmed by Doris Fisher and her sons William, John and Robert. Like with a fractional gift, Doris has some discretion to continue hanging pieces at home, or recall a loaned work from the museum. Like a private museum, the Fishers placed strong restrictions on the collection’s exhibition. And by contributing to the building campaign, the Fishers could write-off the costs of preserving the collection on their own terms. The deal extended the Fishers’ influence even more deeply into museum governance. In 2018, Robert succeeded Schwab as board chair.

Offshoring an Endowment

More than half of SFMOMA’s 75 trustees hail from finance, a ratio comparable to the governing bodies of most major museums. In higher education, tightening bonds between university management and the financial industry have been linked to the use of debt-financing strategies that drive tuition costs22. Over the past two decades, colleges have also shifted endowments into private-equity and hedge funds, using offshore corporations to minimize taxes and scrutiny of their interests in, say, fossil fuels23. Museums have similarly sought to maximize endowment revenue in recent years, becoming significant sources of investment capital, fees and returns for the financial and real-estate sectors from which trustee wealth overwhelmingly derives.

The capital campaign for SFMOMA’s expansion, in addition to $305 million for the new building, raised $245 million for the museum’s endowment. Between 2009 and 2018, the endowment nearly tripled to $343 million. Investment income, in the same period, was inconsistent, swerving from losses of $5.5 million to gains of $10.5 million. More steady was the rise of investment management expenses. Between 2012 and 2013, SFMOMA’s outside investment management fees grew nearly tenfold to surpass $1 million, averaging $1.5 million every year since—excluding brokerage fees and commissions. Schwab, who chairs the museum’s investment committee, processes some of these transactions through his eponymous firm24.

So while the deductible donation-fueled growth of SFMOMA’s endowment failed to meaningfully improve wages for most of its workforce, it generated millions for a relatively small group of money managers. This is a hallmark of financial capitalism, wherein profit-making from existing assets multiplies at laborers’ expense. In the nonprofit museum context, it’s rent-seeking, subsidized: The investment capital is wealth that the government would otherwise collect for social provision. With financiers dominating museum boards, it should come as no surprise when institutional decision-making reflects their self-serving investment strategies. And looking more closely at SFMOMA’s endowment, the degrees of extraction are even more pronounced.

In the 2009-2018 period SFMOMA invested increasingly in “alternative” vehicles such as private equity and hedge funds, including through offshore corporations. Its investments outside the US peaked at $91 million in 2016. I found documentation of a small but telling portion: $7.7 million committed to hedge funds managed by Angelo, Gordon & Co., Canyon Capital Advisors and Equinox Partners. The investments flowed through Cayman Islands-based “blocker” corporations that enable nonprofits to avoid taxes on investment-income unrelated to their charitable purpose. The prevalence of this same strategy at elite colleges came to light in the Paradise Papers leak of 2017, part of a trend worsening inequality in higher-education access.

Equinox focuses on gold and silver mining in the Global South, while Angelo, Gordon invested SFMOMA’s money in mortgage-backed securities, essentially betting on the resumption of debt-bundling practices underlying the 2008 collapse. As mentioned, endowment growth does not appear to have improved wages for most SFMOMA workers. In either case, though, the growth is premised on earthly plunder and predatory lending. And the fees to the fund managers—again, a position many SFMOMA trustees hold at their own firms—mint some of the world’s most exorbitant fortunes. Sean Fieler, the president of Equinox, in his spare time funds things like fertility apps designed to surreptitiously discourage women from using birth control25.

One commonality between SFMOMA’s embrace (and defense of) fractional giving and its investment strategies is commercial secrecy, or obscuring the forms and rate of profit-making, only in a charitable context. SFMOMA expanded to accommodate the Fisher loan, ceding curatorial power to collector-trustees. Under Schwab’s oversight, SFMOMA reinvested related tax-deductible endowment donations into speculative ventures, benefitting the financial sector more than the museum workers left to rotate the Fisher Collection. In this light, SFMOMA’s capital campaign resembles a call for ruling-class solidarity, an incentivized opportunity to protect the value of Fisher’s assets with donations buoying peers in a narrow economic elite.

Closing for most of 2020 changed little of this. Remote fund managers continued tending to the endowment, spared losses by the federal government’s infusion of billions in financial products such as mortgage-backed securities. Presumably, the remote fund managers were spared the cutbacks that cost hundreds of museum jobs, generating returns sufficient to fund basic minimum operations: Climate control, security guards, plywood barricades. The relationship between the original and expanded buildings clarified. The Snøhetta addition always appeared to lurk behind Botta’s architecture, but it was a new museum gestating within: During the pandemic, it fully swelled to fit the dimensions of the old, and to function without a public.

Austerity and Diversity

Early last October, when the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art opened for the first time in nearly seven months, I stood before Cut Trees. The top-floor installation by Oakland artist Muzae Sesay consisted of a forbidding black fence, ribboned with the names of Black people killed by cops, between two paintings: With Resilience, Far Too Long and With Roots, Far Too Deep, flag-like compositions mixing chain-link and leaf forms. Because Sesay is one of the Black artists in Nure Collective, which over the summer protested the museum’s institutional racism, the commission risked the appearance of consolation or recuperation. But, according to Sesay, it was in the works beforehand. In either case, the commission concealed a telling contradiction: Sesay was among 135 museum workers laid off months earlier in March.

In 2020, SFMOMA laid off 186 workers, or nearly 40 percent of its pre-pandemic workforce, according to museum spokespeople. Benezra, the director, took a 50 percent salary reduction, and the executive team took a 10 percent reduction for two months, returning to full pay before implementing a 20 percent furlough for the remaining workers. This was despite receiving a $6.2 million forgivable loan through the CARES Act. Announcing the cuts, museum officials cited an $18 million deficit. For the skeleton crew working onsite, management resisted hazard pay and travel compensation, according to the staff union. Contract security guards were also denied hazard pay. Even in a field acutely affected by months-long closures (one report found more than half of American museums resorted to layoffs and furloughs during the pandemic), the uneven depth of SFMOMA’s cuts stood out.

Current workers who spoke on the condition of anonymity described labor practices during the pandemic as the continuation of a trend. With the rise of blockbuster exhibitions, and then the 2016 reopening, more tasks fell with greater pressure upon an atomized workforce. SFMOMA increasingly behaves, they said, more like the corporations that enriched trustees: Accountable to investors—donors—instead of workers or visitors. The Fisher Collection Galleries, which some workers tend to almost exclusively, arrived at the expense of visitor-centered educational and interpretive initiatives long promoted internally. “With the new building, everything had to be bigger and better,” another SFMOMA staffer of more than ten years said. “If your job is logistical and you say something isn’t possible, someone above your supervisor says do it anyway.”

The pandemic worsened the distrust of museum hierarchy, with staff suspecting the layoffs and furloughs were in part previously planned cuts implemented under cover of the pandemic. The staff union’s OPEIU Local 29 representative said they were at least partially “opportunistic.26” The first round of layoffs coincided with the launch of a restructured exhibition development process led by Tsugumi Maki. The former Institute of Contemporary Art Boston officer started in March, without announcement, as SFMOMA’s chief exhibitions and collections officer. “I heard about the restructure minutes after the layoffs,” one worker said. “They were two parts of one plan.”

And then, on May 25, a white Minneapolis police officer named Derek Chauvin knelt on George Floyd’s neck until the 46-year-old Black man asphyxiated and died, prompting nationwide protests. SFMOMA posted a picture of an artwork from its collection, Glenn Ligon’s 1996 screenprint We’re Black and Strong (I). It depicts raised fists and a blank white banner, inspired by the previous year’s Million Man March in Washington, DC, which excluded Black women. Ligon was calling attention to the role of absence in reifying a heteropatriarchal notion of the Black family. SFMOMA’s social media managers, however, seemed to see a generic pro-Black statement. The caption, a Ligon quotation about representation, did not mention Floyd’s death.

Taylor Brandon, who left her communications job at SFMOMA in April, feeling disregarded as the only Black worker in her department, was frustrated by the vague post. It confirmed her belief that when the museum took seemingly-neutral political positions, motivated partly by not wanting to irk donors, it upheld white supremacy. “This is a cop out,” she wrote in a comment. “Having black people on your homepage/feed is not enough.” The comment, in which she called director Neal Benezra and her former supervisors “profiteers of racism,” was quickly deleted. “It was very true of my experience,” Brandon told me in June27. “Speak out, and you get silenced.”

OPEIU Local 29, the union representing hundreds of museum staff, called the deletion an act of racist censorship. Leila Weefur, Elena Gross and the Heavy Breathing insisted SFMOMA post their statement of support for Brandon in place of material commissioned for the closed museum’s website. Nure Collective, a group of ten local Black artists, including Sesay as well as the Oakland multimedia artist Yétundé Olagbaju, also withdrew their web contributions as more stories of prejudiced behavior by senior employees surfaced online. Brandon and Nure, forming the core of No Neutral Alliance, in a letter to museum leadership demanded Benezra resign and SFMOMA replace upper-level staff who’ve “proven their racial bias,” re-examine bias complaints, and bolster programming and career opportunities for Black artists and curators.

What followed was a widely-reported pressure campaign by staff, No Neutral Alliance, and former staff comprising xSFM0MA. Throughout the year, similar campaigns buoyed by the resurgent Black Lives Matter movement addressed racial discrimination in the arts around the country. They published anonymized testimonials, launched petitions and tracked a new wave of union organizing. At SFMOMA, though, the accountability push uniquely rattled museum leadership, prompting loud commitments to corporate diversity planning. By October, SFMOMA’s newly-installed diversity director was sending all-staff updates about museum executives’ personal donations to organizations such as the Anti Police-Terror Project.

xSFM0MA, the group of former workers complementing NNA, in statements sought to connect institutional racism and diminished working conditions, laying blame at the feet of the trustees. The collective pointed out frontline staff are the most racially diverse group of staff and also the lowest-paid, hardest-hit by layoffs and most susceptible to pandemic-related workplace hazards. The group at once called for trustees to personally stanch the layoffs and for those enriched by industries such as arms production or closely tied to Donald Trump to be replaced by workers and ordinary museumgoers. The demands for more democratic institutional governance highlighted a board eager to attach its largesse to galleries, yet reluctant to support staff.

SFMOMA leadership, however, divided the issue of racism from pay and hierarchy. By limiting concessions to the realm of corporate diversity planning, a field premised on addressing interpersonal expressions of bias but not capitalism, according to one of its prominent author-consultants, SFMOMA could appear sympathetic without material change, excluding a new manager in Human Resources. “If you hold diversity training after laying off so many of your lowest-paid frontline workers, what kind of conversation are you having?” Gross, one of the artists to withdraw web programming in support of No Neutral Alliance, told me in an interview. “It’s an echo chamber to make the remaining people feel less bad about what happened.”

‘A Capitalist Investment, Enforcing White Supremacy’

In October, shortly after SFMOMA reopened (it has since closed once again), I went to a protest against “neoliberalism and museums,” as the cut-and-paste flyer read, outside the Exploratorium, the science, technology and arts museum, organized by Amanda Seigel.

The 24-year-old Black artist was laid off earlier that year. Inspired by Brandon, Seigel published an open letter to Exploratorium director Chris Flink, saying he once mistook her for a homeless person as she napped in a staff area before her shift. Seigel, draped in a bomber jacket, at the protest described the historic role of museums in settler colonialism, building to a call for imaginative militancy. “We cannot live in a different system until we dream of a different system.”

Seigel and another Bay Area arts worker, who runs the @SeizeTheMuseums Instagram account, which calls for “full public control of all museums,” spoke for more than an hour to a dozen attendees, including members of the Freedom Socialist Party. Brandon and No Neutral Alliance, though invited by Seigel, didn’t participate in the action. xSFM0MA posted the flyer. There was some talk of marching to SFMOMA following the speeches, but it didn’t happen.

Why the activism around SFMOMA didn’t seem to create a mobilizable base is outside the scope of this article. It did, however, advance a remarkable consensus. From interpersonal experiences of racism, it largely normalized the idea among local artists and cultural workers that museums represent not staff or publics but cabals of collector-trustees. xSFM0MA in a collective statement pointed to this as the source of cascading inequities in need of elucidation: “We think it’s much harder to recognize the significant role [trustees] serve in creating museums as they are today—a capitalist investment, enforcing white supremacy through cultural forms.”

(xSFM0MA sent me detailed responses to several questions for an article I was forced to withdraw from ARTnews. Read the group’s remarks in full here.)

As museum leadership touts newly-acquired works by Black artists exhibited in the Fisher Collection Galleries, officials are suppressing internal organizing or rerouting efforts through the corporate diversity rubric. According to workers I interviewed, communications staff repeatedly forbade unauthorized contact with the media. All-staff Zoom meetings went to presenter mode, with comments disabled, preventing the kind of crosstalk that prompted Garrels “reverse discrimination” comment. “It has definitely stifled conversation,” one employee said. To raise concerns, employees were directed to a web form with assurance entries would be anonymous.

Still the upheaval has alerted staff to their own disruptive capacity. “We are realizing that in all those instances where we felt like imposters at the museum … it was a good thing—a tangible sign that we are not desensitized to the corporate culture of white supremacy,” Maddie Klett, a department assistant, wrote in an essay published by SFMOMA’s own platform, Open Space.

(In February, Benezra announced his resignation, insisting it was unrelated to public pressure.)

“If you’re an art handler you’re moving around millions of dollars of assets for the most privileged people in the world—you know where you stand,” another staffer told me. The worker wondered if the union, which represents various, disconnected departments, can become a greater vehicle of unity and pushback. “My friend is a sheet metal union member, and when something is unsafe they all sit on the ground and wait for a union rep. That’s solidarity.”

Days after the Exploratorium protest, SFMOMA held a “sunshine” board meeting on Zoom. Benezra detailed collections, employee, visitor and trustee demographics, one of activists’ demands over the summer. Between 2019 and 2020 purchases of works by white artists dropped five points to 65 percent, while works by white artists on view increased 15 points to 80 percent. “We do not see much improvement in overall representation,” Benezra said.

Public commenters recognized the steps towards transparency while continuing to criticize the treatment of workers. One of them, Moira Mosley-Duffy, pointedly asked if the museum’s endowment is invested in fossil fuels. Robert Fisher, the board chairman, who runs one of the nation’s main logging companies, was not forthcoming. “I don’t believe our endowment investments are public,” Fisher responded. “It’s a broad based index oriented strategy.”

Benhamou, J. “Donald Fisher, Gap and the American dream. Flashback on a legendary collection.” Judith Benhamou Reports, no date.

Keats, J. “How Billionaire Charles Schwab Brokered San Francisco's New $610 Million Masterpiece -- SFMOMA.” Forbes, 2016.

Vogel, C. “Museum Closes A Bank Deal.” New York Times, 1999.

Itoi, K. “Japanese Profit in Art Sale.” Artnet, 1999.

“SFMOMA 75th Anniversary: Don Fisher,” conducted by Lisa Rubens, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2010.

McAndrew, C. “The Art Market,” Art Basel and UBS, 2020.

“Art and Finance Report 2014,” “Art and Finance Report 2017.” Deloitte & ArtTactic.

Upton-Hansen, C. “The Financialization of Art.” PhD Thesis, the London School of Economics and Political Science, 2018.

Halperin, J. “‘It Is an Unusual and Radical Act’: Why the Baltimore Museum Is Selling Blue-Chip Art to Buy Work by Underrepresented Artists.” Artnet, 2018.

Erskine, M. “AAMD Reverses Its Position: Museums Can Sell Art To Fund Their Operating Expenses - For Now.” Forbes, 2020.

Offering circular filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, 2020.

Horwitz, A. “Who Should Pay for the Arts in America?” The Atlantic, 2016.

Davis, B. “How the Rich Are Hurting the Museums They Fund.” New York Times, 2016.”

Desmarais, C. “Unraveling SFMOMA’s deal for the Fisher Collection.” SF Chronicle, 2016.

Lefebvre, S. “After SFMOMA Cuts Salaries by 20%, Employees Call Out Major Loans Granted to Executives.” Hyperallergic, 2020.

Lefebvre, S. “SFMOMA Union Talks Drag Over Cost-of-Living Raise Proposal.” KQED, 2018.

Follas, E. “It Belongs in a Museum: Appropriate Donor Incentives for Fractional Gifts of Art.” Notre Dame Law Review, 2008.

“SFMOMA 75th Anniversary: Richard Greene,” conducted by Lisa Rubens, 2007, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2008.

“SFMOMA 75th Anniversary: Neal Benezra,” conducted by Richard Cándida Smith and Lisa Rubens, 2007-2008, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley;

Kroll, A. “The Secrets of a Ring-Wing Dark-Money Juggernaut—Revealed.” Rolling Stone, 2019.

Lefebvre, S. “Special Report: ‘Toxic donors’ are coming under fire at art museums — but not in liberal San Francisco. What will SFMOMA do?” Mission Local, 2019.

Eaton, C. et al. “Bankers in the Ivory Tower: The Financialization of Governance at the University of California.” UC Berkeley Department of Sociology, 2013.

Saul, S. “Endowments Boom as Colleges Bury Earnings Overseas.” New York Times, 2017.

Data in this section gathered from SFMOMA 990s.

Glenza, J. “Revealed: women’s fertility app is funded by anti-abortion campaigners.” the Guardian, 2019.

Lefebvre, S. “SFMOMA Staffers Condemn ‘Racist Censorship’ and Institutional Inequities in Letter Calling for Change.” ARTNews, 2020.

Lefebvre, S. “SFMOMA Faces Censorship, Racism Accusations Over George Floyd Response.” KQED, 2020.

1) thank you for your service 🙏

2) this reminds me of mark lombardi in the best way... as well as the 2009 documentary ‘the great contemporary art bubble’

3) when I worked at gap I used to go visit the fisher collection in the main building on folsom. it always creeped me out... felt like a room full of moldering capital. which it was, lol. (also probably the only chance to see a bruce nauman neon piece that someone forgot to turn on)

Superb article. I have shared it on Twitter and FB, hopefully some people in the artworld are curious and literate enough to read and appreciate the work and thought that has gone into it.

Myself I am in the process of creating a major art prize for the San Francisco Bay area artists, to help remedy the ultra-ultra-uberclass squeezing going on there in every dimension from housing to closed art galleries to virtually no art press or analysis. It's disgusting, no one does a thing for artists - only TO them.

But what does one expect from a society that would accept 1.7 Trillion in tax cuts to the wealthy while continuing to saddle students with a similar amount of debt, rather than the other way around?